Game Design Workshop

-

A simple introductory exercise of game design for 4 players.

-

Picking the core game elements of a digital game to create a similar board game experience.

-

Developing a conceptual game with the theme “The Alien in the Submarine” in just two hours.

-

Creating a board game where players collaborate to achieve their goals.

Aalto’s Devlog #1 / 21st - 25th August 2023

Exercise 01

From point A to point B

Team: Shamit Ahmed, Antti Kangas, John Emslie, Néstor Feijoo Melián

4 Hours

What makes a Game?

Theory

In the introductory lecture of the Master of Arts in Game Design and Development, we discussed the definition of ‘Games’ and in the process, we discovered many games that break this rule.

Exercise

‘Create a board game where players travel from Point A to Point B’

“A game is an interactive structure of endogenous meaning that requires players to struggle toward a goal.”

This definition of games by Greg Costikyan was the focus of the introductory lecture in the Game Design workshop. ‘What makes a game?’ Is a very broad question, but this definition dissects it in several important elements:

Player: The participant(s) of the game

Interactivity: The influence of the player in the game

Structure: Rules of the game

Endogenous meaning: The Magic Circle, which is the frame where the rules of the game apply

Struggle: The effort made by the player and the challenges they must overcome

Goal: The objective of the game

Of course, there can be games that explore the limits of these fundamentals and sometimes the lines are blurred. On the one hand, we discussed many examples that defy this definition and on the other hand, we explored situations that focused on each one of the elements listed above.

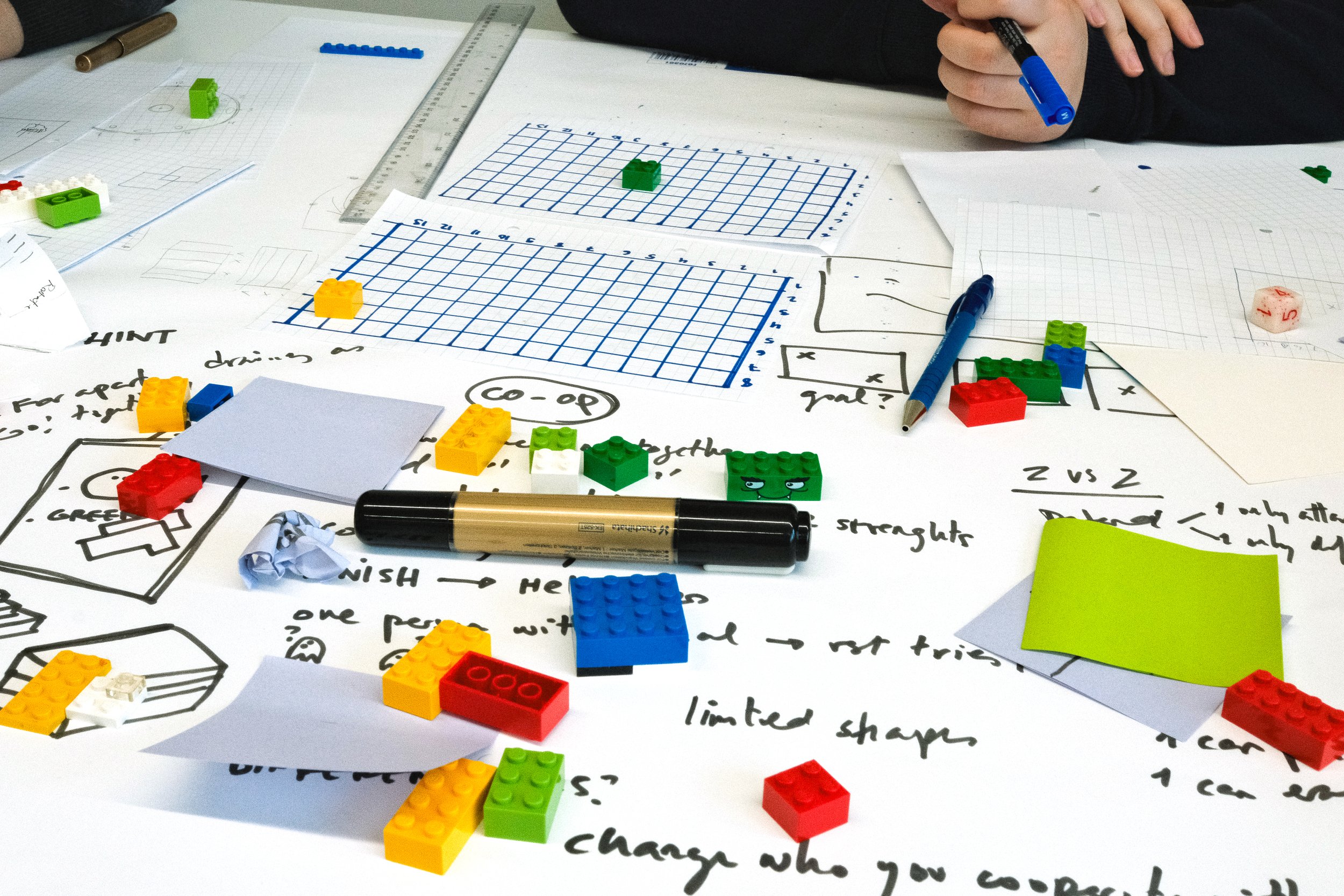

The game

After our first Game Design lecture, our task was to come up with a basic board game prototype. The task was easy: Make a game for four players, moving from Point A to Point B. Nothing fancy or pretty. Just a sketch for a game in which we could make quick tests and iterations on the go.

Immediately after our break, we started bouncing some ideas and one of the premises stood out from the rest:

“What if instead of four players reaching towards a goal we had four goals and only one player?”

This idea meant players would be fighting to move one token towards their individual goals, creating a strategic push-and-pull situation. We set up a board with goals in each corner, and the movement was dictated by poker cards since each of the four suits could represent a player.

We faced immediate issues: The large size of the board made the gameplay tedious, and the game began to turn into a relentless cycle due to every player moving the token toward their direction only for it to be directed elsewhere by the next player.

In the first iterations of the game, we made the board smaller, reduced the number of cards used, limited player movement only forward and tried different win conditions. We even modified the board to create movable parts!

The game was slowly taking shape but a significant problem popped up during the endgame: the game could not be finished. Whenever one player was about to win by reaching their goal, their turn would end. The next player would then move the token towards their goal, stopping the previous player from winning. This process would repeat indefinitely, creating an endless loop.

To fix this, we gave the picture cards some special tweaks. We also put players in teams to help each other win the game. The picture cards let you move the token anywhere on the board, change the turn’s direction, and even switch teams.

This process led to several more iterations as we played and tested our game, each leading to new challenges and insights. We also discovered that some of the special movements should be replaced or limited. After all this iteration we came up with a functioning prototype ready to be tested the next day.

Playtest and Conclusions

The day of the playtest for our first board game arrived. We felt a mix of nervous excitement. Would players enjoy the game? Would they understand the rules?

As the playtest began, we were very surprised with the outcome of the gameplay. The players had a good time and they quickly understood the rules. They collaborated with their partners, switched teams and strategized their moves.

An interesting situation unfolded, one that we hadn't anticipated: One of the players asked her partner if she could show him her cards. He quickly replied that he wouldn’t like to do so because at any given time they could change teams. This response surprised our team because we had been debating if we should include a rule prohibiting them from showing their cards to other players. The fact that one of the players used a mechanic from the game to get to that conclusion was a very pleasing outcome of this playtest.

While there was positive feedback, we also identified areas for improvement. Everyone agreed that the game elements were too basic and there were no story or visual elements. Seen from the outside, players seem to be gambling on a makeshift poker table. This was, of course, a result of a very short exercise where we focused on getting the rules and mechanics right.

In conclusion, observing players dive into the game we created, interact with mechanics that we brainstormed, and solve problems we had set, was a deeply rewarding experience. These game design exercises didn't just teach us how to build a game but demonstrated the crucial role of playtesting and continuous iteration in the process of game development. Pushing boundaries, receiving and applying feedback, and refining our designs were all integral to our journey and we eagerly look forward to the new challenges ahead.

Exercise 02

Digital Game to tabletop experience

Team: Supriya Dutta, Fu Wei, Néstor Feijoo Melián

2.5 Hours

What is Game Design?

Theory

The second lecture of this course addressed subjects like the MDA Framework (Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics), important aspects that must be taken into account while designing a game and the iterative process of prototyping games.

‘Turn a Digital Game into a Board Game keeping its basic elements’

Exercise

“Game design is the process of creating the rules and the content of a game with restrictions.”

The game

Our goal in this exercise was to create a board game based on a digital game. Since we had a three-person team for this task, we started sharing some video games that came to our mind in the first minutes. We brainstormed games that had simple mechanics and after sharing some ideas, we thought that mobile games might be a good fit for this project.

After this brief brainstorming session, we chose Candy Crush for this exercise. We dissected its mechanics, rules and elements and we tried to boil down the basics of this very popular game. The match-3 mechanic is obviously the chore element of this game, but we also wanted to introduce its sense of casual game and its vocabulary elements into our prototype.

Given that this was a very short assignment we dove right into prototyping the game. We first experimented with the board and the colour candies. We iterated a bit with the sizes and amount of types of candies (colours). We balanced it so a maximum of four players could be playing by taking turns. We also had to come up with special rules for the board game, and at this point we had to separate from the original digital game. We included a ‘collecting candy type’ goal. This means that the goal of each player is to collect all five colours. They will do so by matching three or more, and keeping one of the candies with themselves and discarding the rest. Once they do so, they should place three new random candies on the board. We also introduced the concept of 'combos'. By lining up four or more candies of the same colour, players receive an effective ‘power-up’ card. For example, the 'Candy Bomb' card allows them to choose a colour and make the other players discard all the candy of that colour.

The tabletop game was coming along, and we wanted to make sure this was an engaging experience for players. We added a rule to make players socialize more and interact with each other. When claiming one of the power-up cards, they had to shout out loud the name of the card that they wanted. We made ‘Sweet!’, ‘Tasty!’ and ‘Divine!’ special cards. All these cards had the same special abilities, but we thought that it was a good idea to keep players active during the gameplay and these memorable sounds are reminiscent of the original game that we were emulating.

We suddenly realized that we were out of time, so we let everything ready for next day’s playtest and called it a day!

Playtest and Conclusions

We set the game up and called out for three volunteers. Candy Crush enthusiasts were quick to recognize our inspiration by identifying some jokes that we wrote on the borders of our game board and happily joined in. We went by the rules quickly, and since everyone had played the digital game before, it was a smooth onboarding for this tabletop experience. A quick 15-minute playtest session commenced.

As soon as the game started, we noticed that players were engaged with the experience. They got excited when they made accidental combos, shouted ‘Sweet!’ to claim their power-up cards, and inspected the board for needed candies. When the time was over, all of them wanted to continue playing -none of them had time to win the game, but one of the players was very close-, they said that they enjoyed their time playing and that the additions we made to the game made sense with the feel of the original game.

There were some balancing issues with the amount of combos generated by the randomness of the candies, but they benefitted two of the three players, so it was not that unfair at the end. We noticed that some of the players were keeping a large amount of special cards in their hands at the last part of the game, so I reckon that we should limit the amount that they keep in hand or facilitate a bit their use. In any case, it was a great surprise to see what you are capable of making in two hours with a bunch of post-it notes and a pen.

Exercise 03

The Alien in the Submarine

Team: Hanzhi Zhang , Hedi (Moonatic), Néstor Feijoo Melián

3 Hours

Theory

Chance and Skill

Balancing between chance and skill is pivotal in game design. Skill-based games draw players in with challenging tasks and competitive spirit, rewarding meaningful decisions. Meanwhile, incorporating chance can add game variation, reduce predictability, and facilitate surprises, thereby introducing a sense of realism. Managing the impact of skill and chance is not an easy task, but when done right, it can greatly enhance the game experience, creating rich, engaging dynamics.

Create a board game that fits the theme: “The Alien in the Submarine”

Exercise

This graph is a good example of how the amount of dice changes the odds for different numbers.

The game

The third day of the workshop started with the playtest of previous days and it was followed with a lecture about chance and skill in games. After that, we were assigned new groups and an exercise: The goal was to create a board game that went with the theme: “The Alien in the Submarine” and that used tiles as an element of the game. We only had two hours to complete the design, so we gathered our materials and started brainstorming.

We shared ideas on how a submarine looks like a spaceship in a way. Then we started imagining how the Alien’s life would be in the submarine. Was it damaged? Did he need to eat or breathe?

Suddenly, we envisioned a game where an Alien and a human were locked in a submarine. They needed to work together in order to reach the surface, but the human was running out of oxygen and the Alien was getting hungry. They needed to collaborate together to gather resources like food and oxygen and, to repair the rest of the submarine, they should find items exploring the tiles around the submarine. The tile exploration became a central part of gameplay and we spent some time deliberating on how to make it exciting. In the requirements of the assignment stated that we should prioritize strategy over luck, so we decided to go with a narrative placement of the tiles.

For the human player, running out of oxygen was a constant threat and for the Alien player, not eating for too long could also mean that the human was his only food source. This created a sense of urgency that pushed players to balance their resource management with their exploration efforts.

The playing pieces were the Alien and the human, each with their own special abilities. The Alien could use the hook situated in the bottom part of the submarine, whereas the human was able to use the periscope to locate items around the watercraft.

The game also integrated a timer system with respect to the oxygen level and the Alien's hunger. A measure of oxygen and hunger was marked on the board and the players had to manage and balance both while driving the story forward and ensuring the discovery and repair of the different parts of the submarine.

The whole process of creating the board, story and basic rules of the game took us too long to create a proper playtesting and we were running out of time. We decided to eliminate the element of the human and we kept the alien as the central part of the game. As a result, we came out with a narrative survival game for one player. This meant that one of us should be the ‘Game Master’ in the next day’s playtest. There were many doubts about how the game would unfold, but our time was over and we had to leave it like that.

In perspective, coming out with all these ideas and prototyping them in just two hours was an achievement, but at the moment felt like we were too focused on following the theme and forgot a bit about game design. Anyway, the day was over and the playtest was ready for tomorrow.

Playtest and Conclusions

We faced this playtest with a mix of uncertainty and doubt. At the moment of setting up the game, many of our colleagues were intrigued by the unique concept we had created. The shift from a multiplayer to a single-player game with a 'Game Master' raised eyebrows, but also piqued the interest of our volunteer.

As a Game Master, I had no idea how to get the gameplay going, since we didn’t have enough time to make clear rules and balance the elements in the gameplay. As a result, I decided to add mystery to the story and tell the player the rules of the game would unfold as he explored. This was not the original idea we had planned, but it seemed to engage the player. While the player moved through the submarine, he discovered a new tool to keep exploring and I improvised a story so he could follow along, all the while battling the constant struggle of maintaining oxygen levels.

However, despite the initial intrigue, the lack of concrete rules and a clear end goal hindered the player's efforts to explore, and the oxygen levels were going down too fast. As a result, I had to stop the gametest and we went right into the discussion.

In the discussion, we concluded that our game's concept was interesting, but the execution needed improvement. Participants found the idea of survival for one player unique, but the unclear rules made it difficult for the player to strategize. The concept of the 'Game Master' also presented a challenge. While it added a storytelling aspect, it was difficult for the Game Master to balance the game due to the absence of clear rules.

I believe that with more time to iterate, we could have managed to reach a fun and interesting game mechanic. It's a reminder of the importance of not only having a strong conceptual idea but also ensuring that it's properly executed, with clearly defined rules and balanced gameplay.

Exercise 03

A Cooperative Experience

Team: Fatemeh Amereh, Melanie Carolin Wigger, Nina Tepponen, Néstor Feijoo Melián

4.5 Hours

Meaningful Decisions

Theory

The final lecture of this course focused on the decisions made by players during a game. A game should be interactive, and therefore meaningful and meaningless decisions are fundamental to keep players invested in the game. But there are also blind decisions, tradeoffs and dilemmas that we can use in game design. Designers should be aware of aiming of an optimal amount of decisions and it is a good idea that players understand the consequences of their actions. Another big topic discussed were the rewards and punishment that players get, and we analyzed several interesting examples of games that use their rewards or punishment as a key element of the design.

“Create a cooperative board game”

Exercise

“Games are a series of interesting decisions.”

The game

After a week of coming up with different games our creative juices were running low. Our final assignment required a cooperative approach to a board game and in the first brainstorming session we tried to come up with mechanics and rules that required players to work together. There were many ideas and possible scenarios, but we didn’t find one that excited us to keep developing. We were aware that we had a couple of hours left the next morning, we chose to wrap up and recharge at home.

Playtest and Conclusions

The day of the playtest for our first board game arrived. We felt a mix of nervous excitement. Would players enjoy the game? Would they understand the rules?

As the playtest began, we were very surprised with the outcome of the gameplay. The players had a good time and they understood the rules quickly. They collaborated with their partners, switched teams and strategized their moves.

An interesting situation unfolded, one that we hadn't anticipated: One of the players asked her partner if it she was allowed to show her cards. He quickly replied that he wouldn’t like to do so, because at any given time they could change teams. This response got our team by surprise, because we had been debating if we should include a rule prohibiting them to show their cards to other players. The fact that one of the players used a mechanic from the game to get to that conclusion was a very pleasing outcome of this playtest.

While there was positive feedback, we also identified areas for improvement. Everyone agreed that the game elements were too basic and there is no story or visual elements. Seen from outside, players seem to be gambling on a makeshift poker table. This, of course, was a result of a very short exercise where we focused on getting the rules and mechanics right.

In conclusion, observing players dive into the world we created, interact with mechanics that we brainstormed, and solve problems we had set, was a deeply rewarding experience. These game design exercises didn't just teach us how to build a game, but demonstrated the crucial role of playtesting and continuous iteration in the process of game development. Pushing boundaries, receiving and applying feedback, and refining our designs were all integral to our journey and we eagerly look forward to the new challenges ahead.

More from Aalto’s Devlog:

-

Untitled Penguin Game (1/3)

Period 2 - Game Project I

-

Airplane control and procedural map in Unity with C#

Period 1 - Software Studies for Game Designers

-

Game Jam: Mamapato

Period 0 - Introductory Game Jam